By the early 1960s, the news media were closing in on an era of relative equilibrium, at least in the marketplace. While there were still competitive daily newspapers in some communities, the trend was inexorably toward local consolidation and monopoly. Broadcast television was settling into an oligopoly of three networks with scores of local affiliates that owned exclusive licenses to valuable airwaves. Equilibrium meant, for decades to come, massive profits for the owners of these enterprises.

Over four days in 1963, beginning November 22 with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, TV news conclusively claimed a new and lasting mantle: the place where most people got vital news. The stars of TV news – actual journalists in those days – became part of Americans’ households.

Over the past weekend, CBS marked five decades since that grim weekend by streaming its contemporaneous coverage of the killing and aftermath. The stream was more than a history lesson, though: the network was also recalling its own ascension into journalism’s highest realm – an achievement that owes most to to the relentless professionalism of Walter Cronkite and his colleagues during those days.

In 2013 the CBS web stream, and the way the company used it, came in a vastly different context. It was just one of many fast-moving situations in the media business – most involving enterprises that weren’t in the realm of anyone’s imagination 50 years ago – that we saw this Nov. 22-26. They included the sale of a web news startup to another startup; an apparent shakeup at a major business news and information service; and the hiring of a TV superstar by a web company that, by today’s standards, is itself almost old media.

All of this reflected a news and information ecosystem that is seeking a new equilibrium. But don’t hold your breath on this one. We’re in the relatively early days of a messy transition to what (if we do this right) will be a vastly more diverse, and therefore healthier, ecosystem when viewed as a whole – but one that will remain, close to the ground, awash in experimentation, turmoil and change.

The higher-minded (and more financially secure) CBS of a half-century ago aired its JFK coverage without a single advertisement, as did the two other networks of that era. But while CBS deserves credit for putting up the stream this year, to watch it – or any of the short segments CBS pulled out of it – you had to sit through a pre-roll ad. If you stopped the main stream and came back, you got another ad. The company was monetizing, as we say today, but the way it did so was clumsy bordering on cringe-inducing – including, no kidding, a life insurer’s ad preceding JFK funeral footage. Meanwhile, CBS had sent takedown notices to Google’s YouTube (and presumably other sites) ordering the removal of segments of this coverage that other people had posted, notably the overwhelming moment when a close-to-tears Cronkite read the official confirmation of Kennedy’s death. The CBS message: We alone will use and profit from our film of this public tragedy. This was obnoxious, in my view, but CBS did have the right, sad to say, to abuse the copyright system in this way.

Traditional media’s relationship with the Web includes competition with it. During the weekend came the confirmation of a TV star’s move to the web. Not long after luring the talented and prolific David Pogue away from the New York Times, Yahoo hired Katie Couric as a “global anchor,” whatever that means. Both hires are part of a major media/news push by the Internet company, founded in the 1990s, that CEO Marissa Mayer and her colleagues are struggling to reinvent for the 21st Century.

I don’t claim to fully understand what Yahoo is doing with these and other media moves. What most people don’t realize, however, is that its reach is beyond enormous when it wants its still-huge user base to pay attention to something. If advertising has a future at all, Yahoo has every possibility of being one of the organizations that profit from it.

The long weekend also brought more details about what is sounding like serious rethinking, if not upheaval, inside the Bloomberg news and information organization. As the Times reported, some executives – all of whom insisted on anonymity, which raises questions about their (and the story’s) credibility – have “begun to question the role of the company’s news operation.” What we know for sure is that about 2 percent of the journalists have lost their jobs there. The company’s own credibility has taken a hit amid believable reports that business priorities led to the killing of a story about Chinese politicians, though executives have denied this.

Financial considerations have always affected journalism, at all companies, some more blatantly than others, though in recent decades most traditional journalism organizations have insisted they prevented corporate interference. But in an era when hyper-competitive enterprises vie for ebbing and emerging markets, the editorial and business sides of almost all for-profit media operations will clash and cooperate. And it should surprise no one that Bloomberg, which overwhelmingly makes its money on the financial data portion of its business, constantly rethinks the proper personnel mix.

Much, much further down the media food chain came the news that PandoDaily, a startup media company based the Bay Area, was acquiring another financially struggling startup, NSFW Corp. The deal was scarcely noticed outside the still somewhat insular world of tech journalism, but it “caused more than a few tremors in the world of new-media startups,” as GigaOm’s Mathew Ingram noted. Count on a lot more tremors like that one, then, because in a market where there’s so little barrier to entry, lots of people will enter and there will be lots of competition – and, besides, most startups fail.

That’s actually good news, if not for the ones that fail (as I did in an abortive media startup almost a decade ago). It’s good news because it means we’re in a fiercely competitive market, awash with experiments and ideas and, in some notable cases, major-league new investments. It’s also good news because a diverse media ecosystem could produce the kind of variety, at all levels of quality, that will create a better set of news and information choices, overall, than the much less diverse – if vastly more stable – environment whose loss we tend to lament.

Yes, we are losing, at least for the short term, some things we will miss – including the calming authority and integrity of people like Walter Cronkite and his team. But I’m ready to live in a world of diversity and choice, and the complexity that results, where I have to make more of my own decisions about who and what to trust – and where I can be better informed in the end.

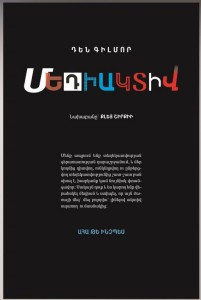

Armenia-based “Journalists For The Future” has led a project to translate Mediactive into Armenian, and I visited there last week to help launch the new edition. I met some extraordinary people and learned a lot about the media scene there.

Armenia-based “Journalists For The Future” has led a project to translate Mediactive into Armenian, and I visited there last week to help launch the new edition. I met some extraordinary people and learned a lot about the media scene there.